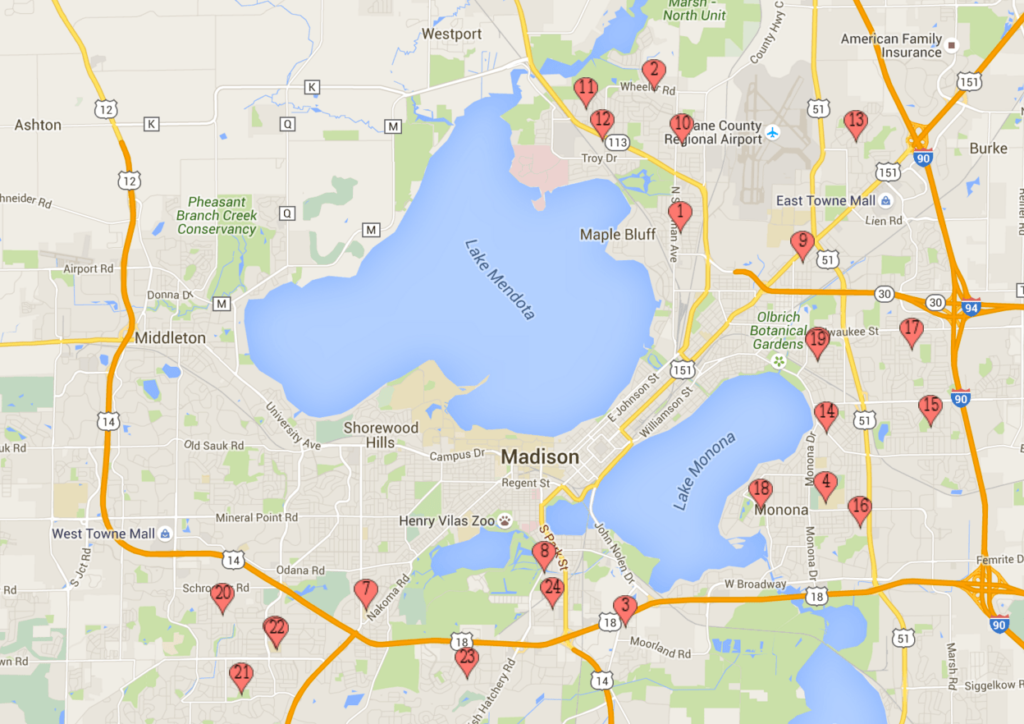

Everyone in Madison knew to avoid Badger Road.

It was 1996, and the city was celebrating being christened the best place to live in America by Money Magazine:

This year, Madison (and the rest of Dane County) earns the No. 1 position among the 300 biggest U.S. metropolitan areas in our 1996 Best Places to Live in America ranking. It snagged the top spot because apparently someone forgot to tell the folks in Madison that life is supposed to be full of trade-offs. The 390,300 residents of Dane County, 80 miles west of Milwaukee in south-central Wisconsin, have a vibrant economy with plentiful jobs, superb health care and a range of cultural activities usually associated with cities twice as big. Yet this mid-size metro area also offers up a low crime rate and palpable friendliness you might assume are available only in, say, Andy Griffith’s Mayberry. The news that the great Dane County is top dog this year probably won’t surprise the region’s residents. More than 90% of Madisonians rated their quality of life good or very good in a recent survey. Since the cosmopolitan Madison area — the city accounts for about half the county’s population — is surrounded by Wisconsin’s everpresent dairy farms, it seems only right to toast 1996’s No. 1 big cheese with a wedge of aged Wisconsin cheddar.

Still, despite the excellent quality of life, most everyone had, at one time or another, been made aware that the neighborhoods around South Park Street were “dangerous”; that wasn’t such a big deal, though, because no one you knew ever went there.

Madison’s Crescent

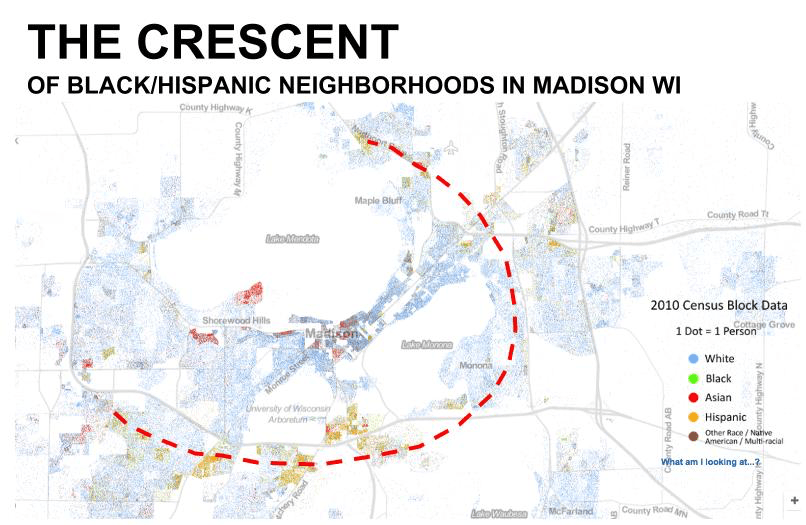

In 2016, a blogger named Lew Blank observed that the racial distribution of Madison neighborhoods formed a crescent:

When you look at Madison’s Racial Dot Map, you notice a pattern. The bottom and right sides of the map hold the majority of the black and hispanic population. It forms a curve almost – starting in the South Side, crossing along the east side of Lake Monona, and ending at the Northeast Side. I dub this curve-like chain of black and hispanic neighborhoods “The Crescent”.

This crescent was also seen in poverty indicators:

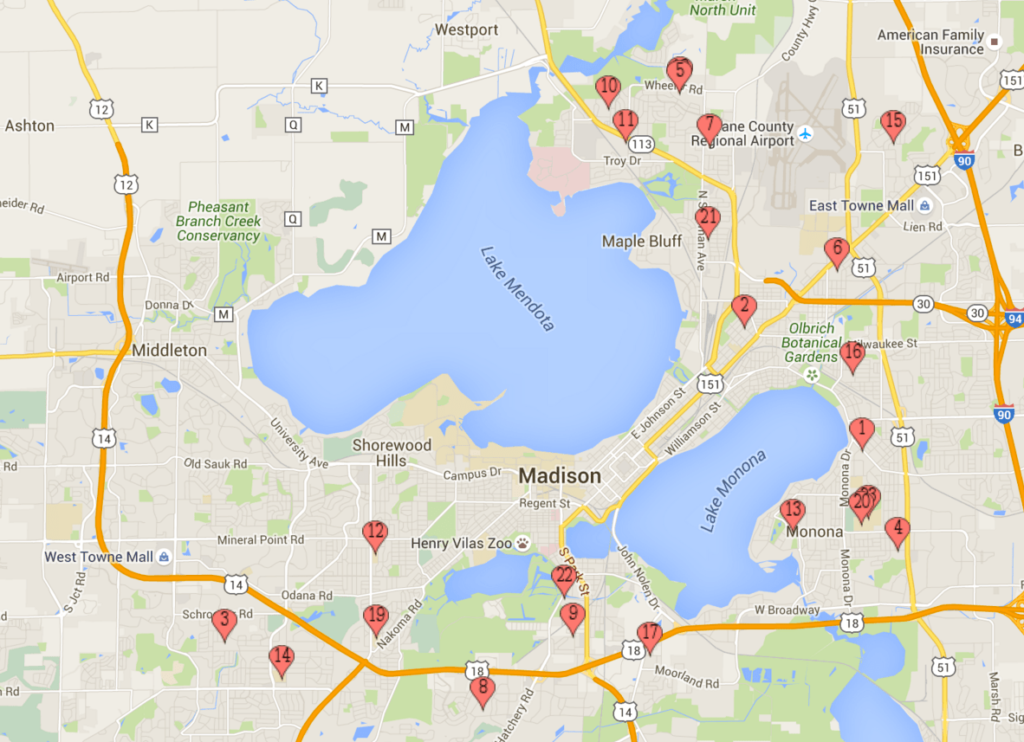

Shown below is a map of every single school in Madison with above average usage of free/reduced lunch programs:

That’s right. 23 out of 23 schools in Madison that have above average usage of free/reduced lunch programs all fall along the Crescent.

The deal is, the children who need free/reduced lunch are poor, obviously. So does that mean that the poorest neighborhoods of Madison fall along the Crescent? Unfortunately, that’s exactly what it means.

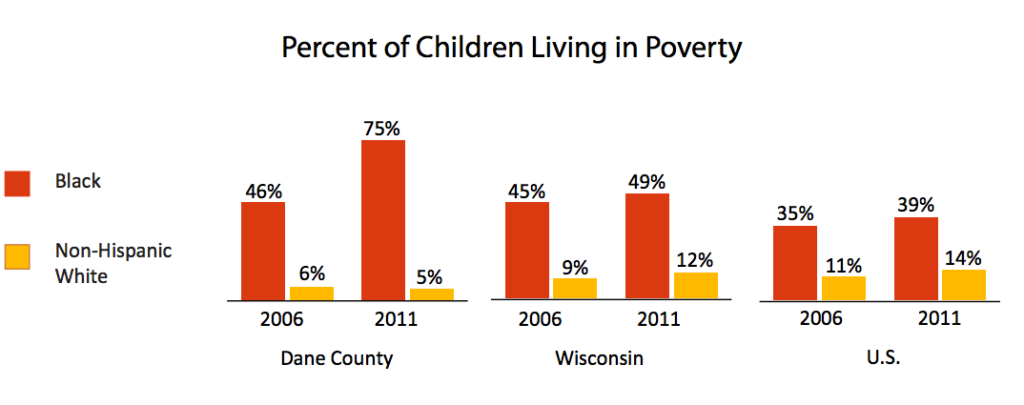

In Madison, a black child is 13 times more likely than a white child to be born into poverty – an insanely high disparity.

So, Madison’s black and hispanic neighborhoods (the ones on the Crescent) are its poorest neighborhoods, and Madison’s white neighborhoods (the ones not on the Crescent) are its wealthiest neighborhoods.

Unsurprisingly, the crescent was also seen in educational outcomes:

It’s clear, then, that schools in the Crescent of poor black/hispanic neighborhoods would be expected to have below-average academic success. And unfortunately, the map below of all Madison schools with below-average reading proficiency rates indicates that this is exactly the case.

Believe it or not, 24 out of 24 schools with below-average reading proficiency rates fall along the Crescent.

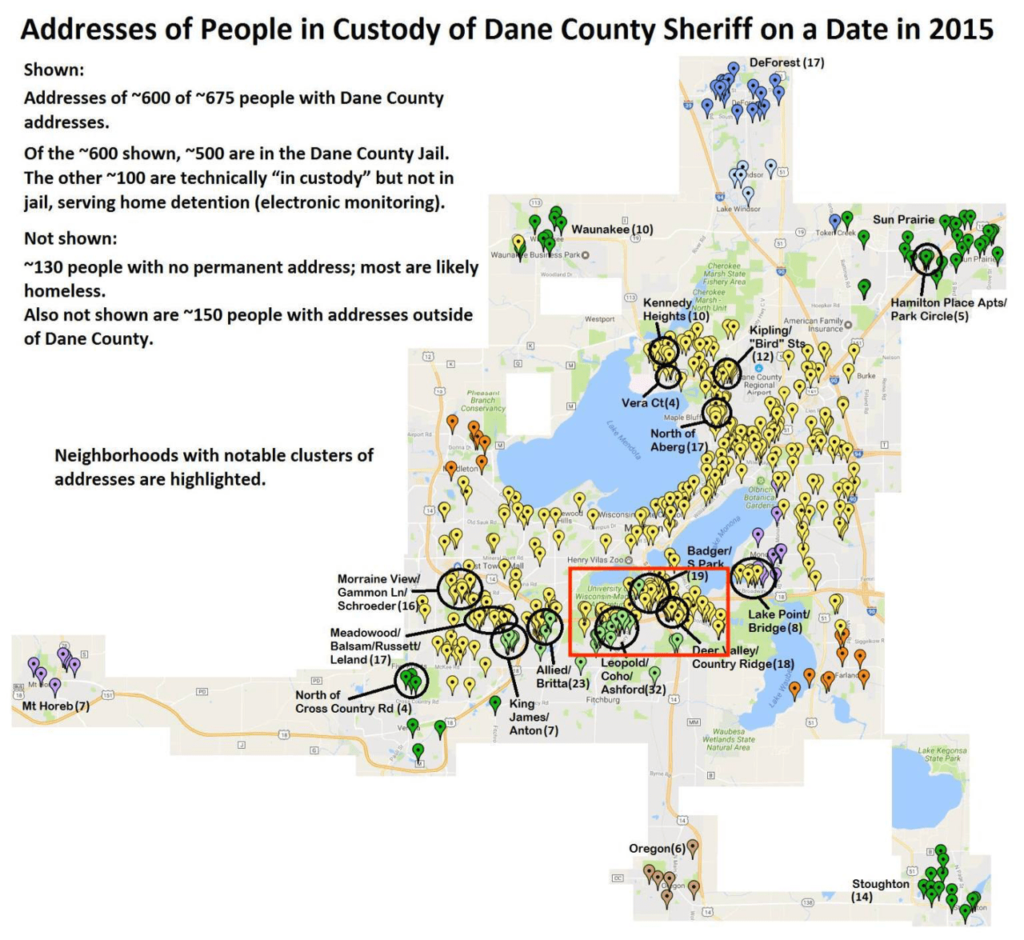

And, of course, crime; I personally added the red box to Blank’s final map to indicate the Badger Road area I mentioned above:

The map below of the addresses of incarcerated Madisonians shows that incarceration in Madison tends to be clustered around the Crescent.

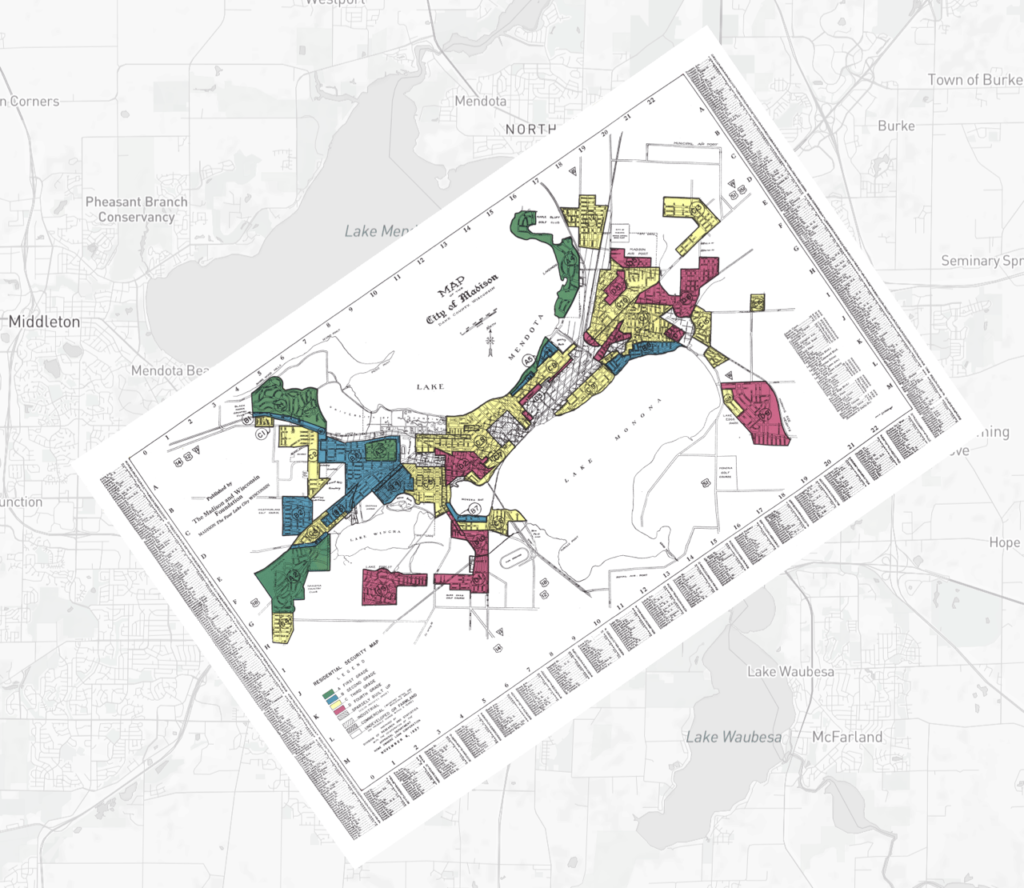

There was one map that Blank was missing though: the notorious Home Owners’ Loan Corporation map. The Home Owners’ Loan Corporation was a federal agency formed as part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal; its purpose was to refinance home mortgages, but as part of the process, the Corporation mapped out U.S. neighborhoods by risk, and by risk, HOLC all-too-frequently meant percentage of non-white people, particularly African Americans. Here was the map of Madison (laid on top of a current map in order to deliver the a north-is-up perspective):

Once you see the crescent, you can’t unsee it. And, relatedly, you can’t escape the impact on Madison. In 2018 African Americans made up 7% of the population but 43% of arrests and 46% of Dane County Jail inmates; African American students were 18% of the school district, but received 57% of suspensions; 10 percent of African American students received an “advanced” or “proficient” score on the math portion of Wisconsin’s standardized testing, while 61% of white students did the same (the proportions were similar for all subjects). Meanwhile the average house price in the Burr Oaks neighborhood (which includes Badger Road) is $145,300; the Madison average is $300,967.

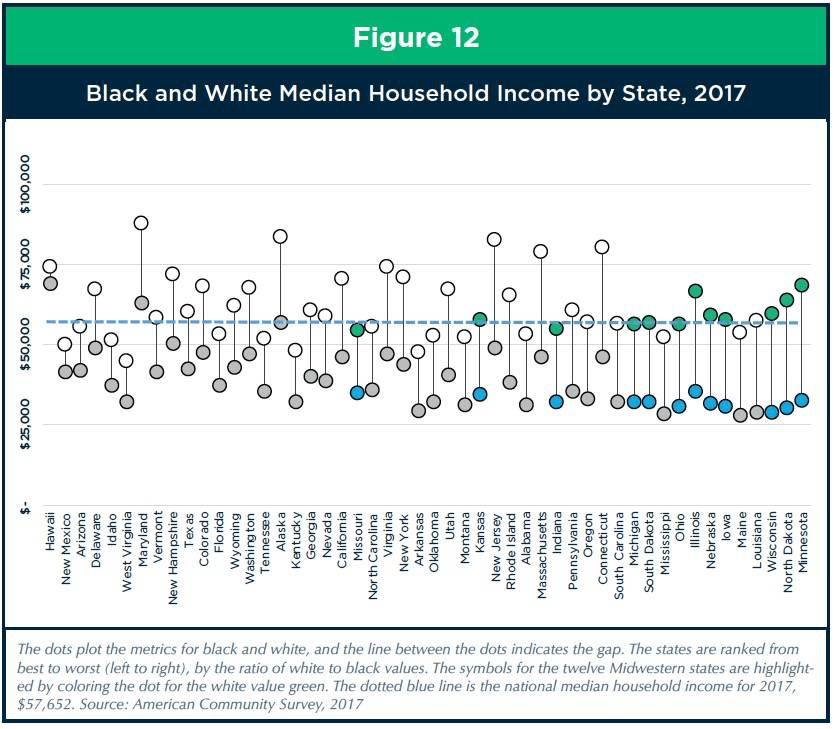

The pattern is even worse in Milwaukee, Wisconsin’s largest city, and the most segregated city in the country; small wonder that Wisconsin ranks so highly when it comes to the disparity between black and white median household income:

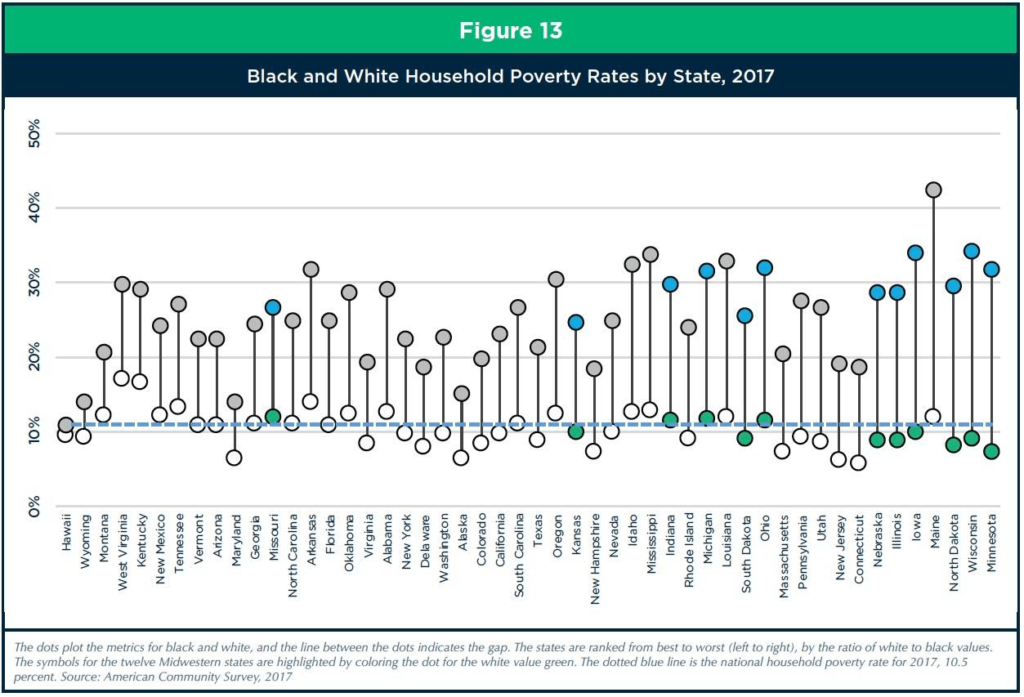

And poverty rates:

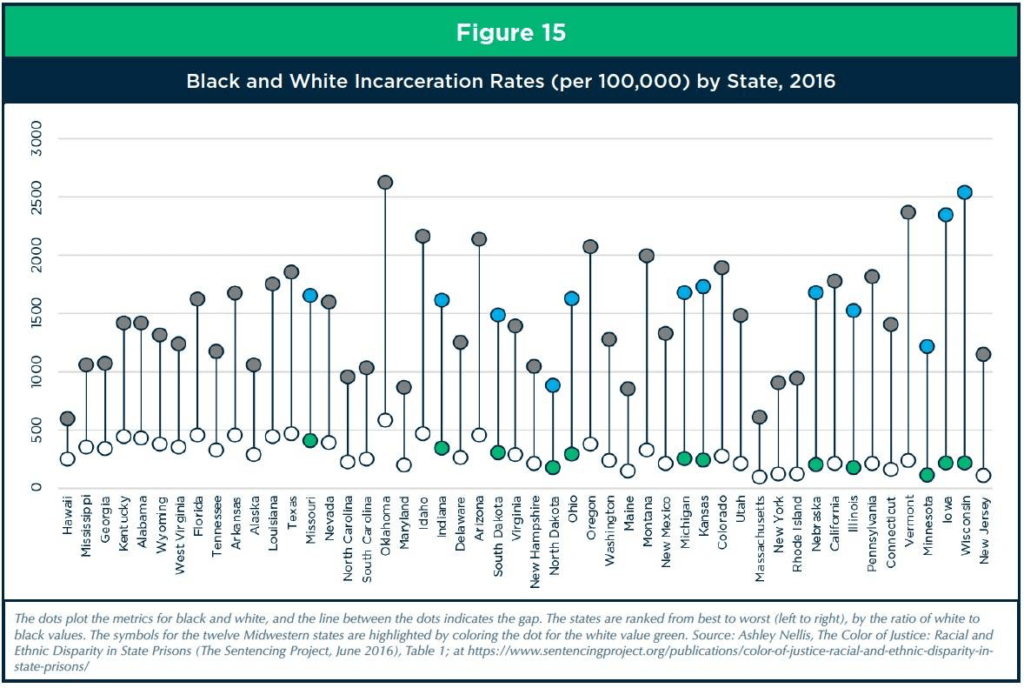

And, as the paper from which these charts are drawn puts it:

Racial disparities in rewards and returns (opportunity, compensation, security) are matched by racial disparities in punishment…Five (WI, IA, MN, IL, NE) of the ten worst-performing states, ranked by the ratio between black and white rates, are in the Midwest. Such disparities, glaring in their own right, also have profound impacts on individuals, families and communities. Incarceration short circuits equal citizenship—the right to vote, educational and employment opportunities, access to housing—in deep and lasting ways.

The one state competing with Wisconsin for the highest measurements of disparity is the neighbor to the west: Minnesota.

Minneapolis and George Floyd

While red-lining helped shape segregation in many cities, Minneapolis was pre-emptive about its discrimination; beginning in the 1910s Minneapolis real estate deeds started to include “Covenants” that explicitly excluded African Americans. A team from the University of Minnesota has been researching real estate deeds to uncover these covenants, and created this striking time-lapse of their spread:

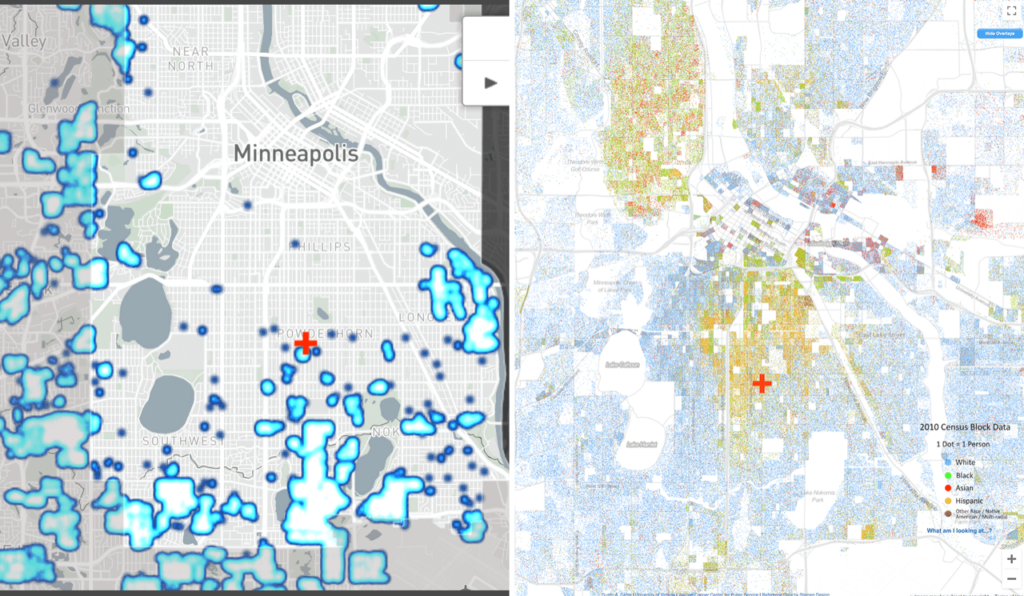

Racial covenants were ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1948, but the effect remains; compare the racial covenant map to the racial dot map Blank referenced above — the blue (which is white people) adheres to the blue of racial covenants:

That red cross, meanwhile, is the location of the homicide of George Floyd, in the decidedly non-blue portion of the map. “Homicide” was the word used by the Hennepin County Medical Examiner, which ruled that Floyd’s cause of death was “Cardiopulmonary arrest complicating law enforcement subdual, restraint, and neck compression”; it is up to prosecutors and a jury to decide if that homicide constitutes murder.

The rest of the country did not take so long: nearly all have seen the video of Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin with his knee on Floyd’s neck for 8 minutes and 46 seconds, even as Floyd first complains he cannot breath, and then, for the final two minutes and 53 seconds, falls silent.

Dust in the Air

The first version of the Hennepin County Medical Examiner’s autopsy, at least the part quoted in the criminal complaint against Chauvin, read a bit differently:

The Hennepin County Medical Examiner (ME) conducted Mr. Floyd’s autopsy on May 26, 2020. The full report of the ME is pending but the ME has made the following preliminary findings. The autopsy revealed no physical findings that support a diagnosis of traumatic asphyxia or strangulation. Mr. Floyd had underlying health conditions including coronary artery disease and hypertensive heart disease. The combined effects of Mr. Floyd being restrained by the police, his underlying health conditions and any potential intoxicants in his system likely contributed to his death.

The underlying health conditions and intoxicants are still in the final report; what has changed is their relative prominence in explaining Floyd’s death. One suspects that in a different world — say, the world that was Minneapolis for most of the 20th century — said underlying health conditions and intoxicants would have been held to be the cause of death, not “Other significant conditions.” Perhaps there would be a two paragraph story in the Star Tribune on page A17, or more likely Floyd’s death would have disappeared into a police filing cabinet, a non-event as far as most of Minneapolis was concerned. At best there would be a murmur to avoid that sketchy Powderhorn neighborhood, a rarely-visited barely-remembered exception to Minneapolis’ status as one of the best cities in America.

Those who knew Floyd or witnessed his death would know better, of course. They would, as Kareem Abdul-Jabbar wrote in the Los Angeles Times, shout “Not @#$%! again!” Abdul-Jabbar explains:

African Americans have been living in a burning building for many years, choking on the smoke as the flames burn closer and closer. Racism in America is like dust in the air. It seems invisible — even if you’re choking on it — until you let the sun in. Then you see it’s everywhere. As long as we keep shining that light, we have a chance of cleaning it wherever it lands. But we have to stay vigilant, because it’s always still in the air.

What made the Floyd story different than all of the surely similar examples that went before it is the Internet, specifically the combination of cameras on smartphones and social networks. The former means any incident can be recorded on a whim; the latter means that said recording can be spread worldwide instantly. That is exactly what happened with the Floyd homicide: the initial video was captured on a smartphone and posted on Facebook, triggering a level of attention to the Floyd case that in all likelihood changed the nature of the autopsy and led to the pressing of charges against Chauvin — a chance, in Abdul-Jabbar’s words, of cleaning at least one spec of that omnipresent dust.

Trump’s Tweets

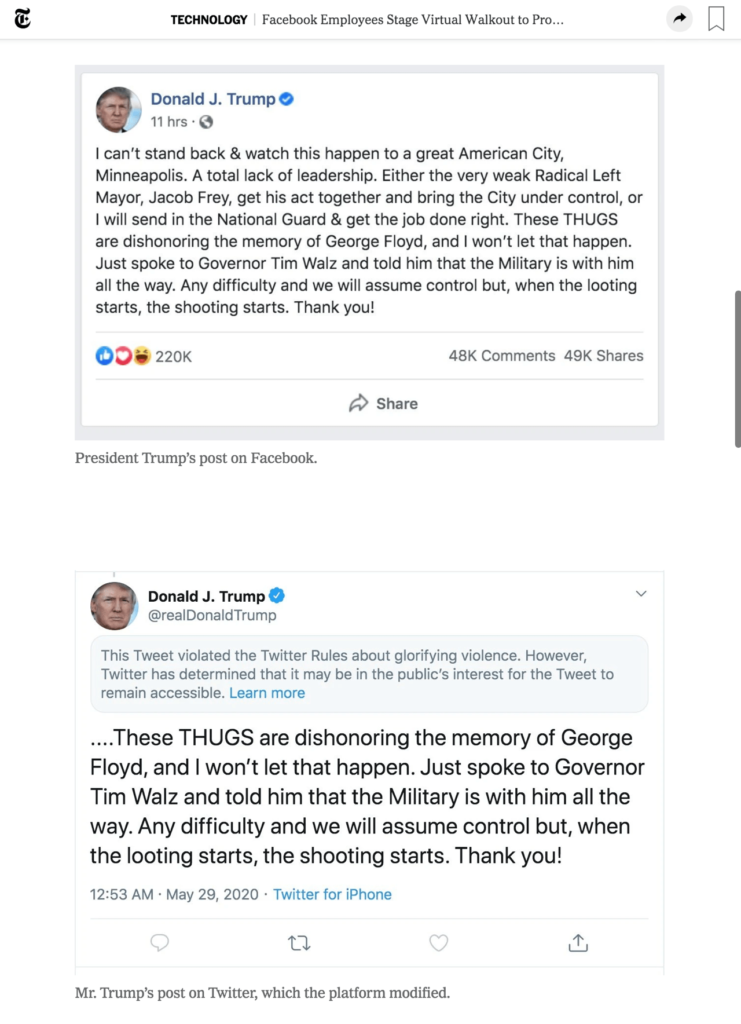

Notably, this is not why Facebook is in the news this week; yesterday hundreds of employees staged a virtual walkout to protest the fact that the company committed, in their mind, a sin of omission: not deleting posts from President Trump. Those posts are copies of Trump tweets, three of which Twitter modified in some way last week. The first two were Trump allegations that voting by mail had a high risk of fraud; Twitter attached a “Get the facts” label that led to a page disputing Trump’s claim.

The more serious intervention came early Friday morning, when Twitter obscured a Trump tweet because it, in their determination, “violated the Twitter Rules about glorifying violence.”

Twitter — at least as far as citing its rules is concerned — apparently objected to the phrase “when the looting starts, the shooting starts,” which is associated with a brutal segregationist police chief from Miami; Trump claimed to not know the saying’s history, but honestly, arguing about that phrase feels like a distraction from Trump’s all-capitalization use of the descriptor “thugs”, a word with significant racial undertones. That certainly seemed to be what the protesting Facebook employees picked up on; from the New York Times:

“The hateful rhetoric advocating violence against black demonstrators by the US President does not warrant defense under the guise of freedom of expression,” one Facebook employee wrote in an internal message board, according to a copy of the text viewed by The New York Times. The employee added: “Along with Black employees in the company, and all persons with a moral conscience, I am calling for Mark to immediately take down the President’s post advocating violence, murder and imminent threat against Black people.” The Times agreed to withhold the employee’s name.

What is notable about that New York Times story is that it reproduces the post (and tweet!) that the employees want taken down:

So did the story I linked to above about that Miami police chief, and countless other publications. Indeed, it seems rather obvious that Twitter’s action — and those objecting to Facebook’s lack of action — ensured that Trump’s tweet would be far more widely read than it might have been otherwise.

It is not clear that this is a bad thing. Trump’s tweet is abominable, but sadly, of a piece with far too many presidents. The Associated Press wrote in 2019:

Throughout American history, presidents have uttered comments, issued decisions and made public and private moves that critics said were racist, either at the time or in later generations. The presidents did so both before taking office and during their time in the White House…

This extends far beyond the founding fathers, most of whom owned slaves, to the 20th century:

The Virginia-born Woodrow Wilson worked to keep blacks out of Princeton University while serving as that school’s president…

Democrat Lyndon Johnson assumed the presidency in 1963 after the assassination of John F. Kennedy and sought to push a civil rights bill amid demonstrations by African Americans…But according to tapes of his private conversations, Johnson routinely used racist epithets to describe African Americans and some blacks he appointed to key positions.

His successor, Republican Richard Nixon, also regularly used racist epithets while in office in private conversations…As with Johnson, many of Nixon’s remarks were unknown to the general public until tapes of White House conversations were released decades later. Recently the Nixon Presidential Library released an October 1971 phone conversation between Nixon and then California Gov. Ronald Reagan, another future president…Reagan, in venting his frustration with United Nations delegates who voted against the U.S., dropped some racist language.

The part about secret tapes is notable: much of this racism — this dust in the air — was in darkened rooms, unseen by the public. Trump, if nothing else, has no need for secret tapes: we have his very public Twitter account, and all indications, particularly in terms of pre-COVID polling, suggest that it massively weakened his reelection bid.

The president’s threats, meanwhile, continue: yesterday Trump demanded governors around the country crack down on the looting that has in several cities followed peaceful protests, saying he would call in the military otherwise. That certainly seems to be, in broad strokes, in line with the tweet Twitter hid — does it matter that Trump stated his position on a conference call and in the Rose Garden instead of a tweet?

In fact, that is what is so striking about the demands that Facebook act on this particular post (beyond the extremely problematic prospect of an unaccountable figure like Zuckerberg unilaterally deciding what is and is not acceptable political speech): the preponderance of evidence suggests that these demands have nothing to do with misinformation, but rather reality. The United States really does have a president named Donald Trump who uses extremely problematic terms — in all caps! — for African Americans and quotes segregationist police chiefs, and social media, for better or worse, is ultimately a reflection of humanity. Facebook deleting Trump’s post won’t change that fact, but it will, at least for a moment, turn out the lights, hiding the dust.

A Gargantuan Force

It is hard to be optimistic about anything at this moment in time. My regular refrain from the beginning of the coronavirus crisis is that the most likely outcome will be the acceleration of trends that were already happening. That is particularly scary given what I wrote back when Stratechery started in 2013, in a post called Friction:

Count me with those who believe the Internet is on par with the industrial revolution, the full impact of which stretched over centuries. And it wasn’t all good. Like today, the industrial revolution included a period of time that saw many lose their jobs and a massive surge in inequality. It also lifted millions of others out of sustenance farming. Then again, it also propagated slavery, particularly in North America. The industrial revolution led to new monetary systems, and it created robber barons. Modern democracies sprouted from the industrial revolution, and so did fascism and communism. The quality of life of millions and millions was unimaginably improved, and millions and millions died in two unimaginably terrible wars.

Another comparison point is the printing press, which I wrote about last year in the context of Facebook:

Just as important, though, particularly in terms of the impact on society, is the drastic reduction in fixed costs. Not only can existing publishers reach anyone, anyone can become a publisher. Moreover, they don’t even need a publication: social media gives everyone the means to broadcast to the entire world. Read again Zuckerberg’s description of the Fifth Estate:

People having the power to express themselves at scale is a new kind of force in the world — a Fifth Estate alongside the other power structures of society. People no longer have to rely on traditional gatekeepers in politics or media to make their voices heard, and that has important consequences.

It is difficult to overstate how much of an understatement that is. I just recounted how the printing press effectively overthrew the First Estate, leading to the establishment of nation-states and the creation and empowerment of a new nobility. The implication of overthrowing the Second Estate, via the empowerment of commoners, is almost too radical to imagine.

And yet, look again at this past week: a century of institutionalized racism in Minneapolis was not necessarily overthrown, but certainly overwhelmed in the case of George Floyd, because of a post on Facebook. Both peaceful protests and wanton destruction and looting were organized on social media. Video of both were circulated around the world via ubiquitous smartphone cameras on said social networks. The Internet is an amoral force — it can effect both positive and negative outcomes — but what cannot be underestimated is how gargantuan a force it is.

To that end, while there is much to fear, there is room for hope as well. I am grateful that I can no longer unsee Madison’s crescent, thanks to a blog post. I am angered by the video of Floyd’s death, and appalled at the dust in the air that yes, I was privileged enough to avoid without a second thought. And no matter what upheaval lies ahead, I am certain that the light that illuminates that dust so brightly can never be put away. There are no more gatekeepers, oftentimes for worse, but also for better.